Rascals case in brief

In the beginning, in 1989, more than 90 children at the Little Rascals Day Care Center in Edenton, North Carolina, accused a total of 20 adults with 429 instances of sexual abuse over a three-year period. It may have all begun with one parent’s complaint about punishment given her child.

Among the alleged perpetrators: the sheriff and mayor. But prosecutors would charge only Robin Byrum, Darlene Harris, Elizabeth “Betsy” Kelly, Robert “Bob” Kelly, Willard Scott Privott, Shelley Stone and Dawn Wilson – the Edenton 7.

Along with sodomy and beatings, allegations included a baby killed with a handgun, a child being hung upside down from a tree and being set on fire and countless other fantastic incidents involving spaceships, hot air balloons, pirate ships and trained sharks.

By the time prosecutors dropped the last charges in 1997, Little Rascals had become North Carolina’s longest and most costly criminal trial. Prosecutors kept defendants jailed in hopes at least one would turn against their supposed co-conspirators. Remarkably, none did. Another shameful record: Five defendants had to wait longer to face their accusers in court than anyone else in North Carolina history.

Between 1991 and 1997, Ofra Bikel produced three extraordinary episodes on the Little Rascals case for the PBS series “Frontline.” Although “Innocence Lost” did not deter prosecutors, it exposed their tactics and fostered nationwide skepticism and dismay.

With each passing year, the absurdity of the Little Rascals charges has become more obvious. But no admission of error has ever come from prosecutors, police, interviewers or parents. This site is devoted to the issues raised by this case.

On Facebook

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Click for earlier Facebook posts archived on this site

Click to go to

Today’s random selection from the Little Rascals Day Care archives….

Surviving tape undercuts officer’s testimony

May 11, 2012

May 11, 2012

“One of the attorneys preparing the appeal brief for Mr. Kelly found a tape of an interview with a child that had been taped over with another interview, but retained the last five minutes. The attorney (described Brenda Toppin’s approach as) ‘not only suggestive, but coercive to the point of brutality. The child’s crying and pleas to stop are met only by Ms. Toppin’s promise to stop when the child said what she wanted to hear’….

“(This discovery) is especially shocking because Officer Toppin denied under oath that she was coercive, suggestive or leading in her interviews.”

– From “What I learned from the Edenton Little Rascals sex abuse trial” by

Moisy Shopper, M.D. (in the peer-reviewed journal Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 2009)

Why we want to forget the panic ever happened….

npr.org

Margaret Talbot

July 15, 2016

“When you once believed something that now strikes you as absurd, even unhinged, it can be almost impossible to summon that feeling of credulity again. Maybe that is why it is easier for most of us to forget, rather than to try and explain, the Satanic-abuse scare that gripped this country in the early ’80s – the myth that Devil-worshipers had set up shop in our day-care centers, where their clever adepts were raping and sodomizing children, practicing ritual sacrifice, shedding their clothes, drinking blood and eating feces, all unnoticed by parents, neighbors and the authorities….”

– From “The Devil in The Nursery” by Margaret Talbot in The New York Times (Jan. 7, 2001)

![]()

What might’ve been: Nancy Lamb at the multiplex

May 30, 2015

May 30, 2015

Ofra Bikel’s eight hours of “Innocence Lost” were surely powerful, but the narrowness of PBS’s audience limited their impact. What if the Little Rascals Day Care case had also inspired a major theatrical release? What if several million moviegoers had watched the dramatic nobody-dunnit even as the real-life Edenton Seven were languishing in jail or standing trial?

For a brief moment, that seemed possible.

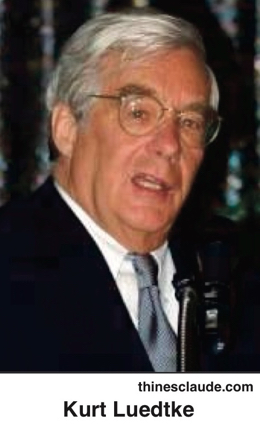

Kurt Luedtke, screenwriter for the ’80s hits “Out of Africa” and “Absence of Malice,” was outraged after seeing the initial “Innocence Lost” in 1991. “You can’t hold people that long without presenting the evidence,” he told the Charlotte Observer.

Now retired and living in Michigan, Luedtke recalls his “indignation mounting and (thinking) I had to do something about the preposterousness of what was going on….”

Alas, his idea apparently made it no further than a preliminary meeting in New York with Bikel and “Frontline” founder David Fanning: “I can’t remember why we didn’t go forward; maybe I had another job.”

What made Mark Everson an expert witness?

July 2, 2012

July 2, 2012

Perhaps the prosecution’s most influential expert witness during the 1992 trial of Bob Kelly was psychologist Mark Everson, director of the Program on Childhood Trauma and Maltreatment in UNC Chapel Hill’s department of psychiatry.

Here’s how Everson responded to a defense expert’s testimony that children are suggestible and should not be repeatedly interviewed: “It’s kind of naïve. It’s the kind of statement you really wouldn’t make if you worked with these kids.”

In a Charlotte Observer interview 10 years later, Everson seemed unmoved by the continuing wave of scientific research exposing the fallacy of “Children don’t lie.” He said he found it hard to believe that every Little Rascals child-witness had been badly interviewed and confused: “There’s so much smoke there, it’s hard to imagine there’s no fire.”

Where there’s smoke there’s fire?

Good lord. I wasn’t surprised to hear such naivete from a juror – “Something must have happened,” one told Ofra Bikel — but from a respected UNC faculty member whose opinion influenced whether Bob Kelly would be convicted and imprisoned?

Last week I emailed two questions to Everson at his Chapel Hill office:

– Have you changed your mind?

– How much credence do you give researchers such as Ceci and Bruck who have demonstrated the unreliability of child-witnesses?

I’ve yet to hear back.

But it’s hard to optimistic about a possible reassessment when Everson continues to choose Kathleen Coulborn Faller as his most frequent coauthor.

0 CommentsComment on Facebook